NepalIsrael.com auto goggle feed

Between the Israeli community of Sha’ar Efraim in central Israel and the Palestinian village of Jalameh in the West Bank, in the heart of one of the most volatile security situations the region has seen in decades, a quiet, daily partnership endures—one that sustains thousands of families on both sides. This is not a political alliance but one rooted in labor: in land, water, sowing and harvest.

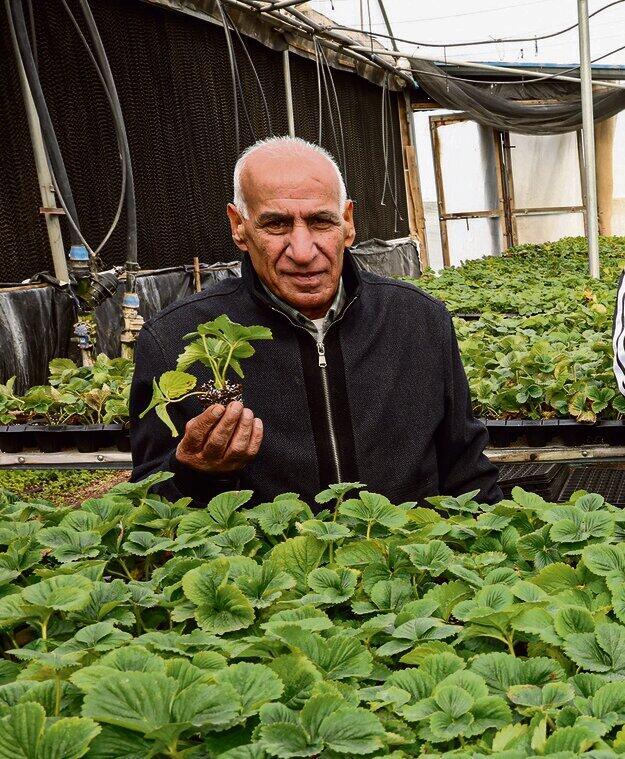

At the center of this cooperation is Samir Moadi, a member of the Druze minority from the northern Israeli town of Yarka. Moadi serves as the agricultural coordinator for the Civil Administration, which oversees civilian affairs in parts of the West Bank under Israeli control. He is also a bereaved father—his son, Cpl. Yosef Moadi, a Golani Brigade soldier, was killed in Gaza during Operation Cast Lead in January 2009. Despite the loss, Moadi chose to move forward, grounded in the soil.

“I continue to carry out my work with dedication because I’ve come to understand that this is the only path to brotherhood and peace,” Moadi says quietly. “A person who works, earns a living and lives with dignity doesn’t seek war.”

The Palestinian agricultural sector relies heavily on the Israeli market. Approximately 65% of Palestinian produce is sold to Israel, amounting to more than 100,000 tons out of an annual 150,000-ton yield. This accounts for about 10% of total produce consumption in Israel.

“If there’s no Israeli market, there’s no Palestinian agriculture,” Moadi says bluntly. “It’s that simple.” Agricultural trade from the West Bank to Israel is valued at roughly 1.2 billion shekels ($384 million) a year. Agriculture makes up around 7% of the Palestinian GDP and employs some 140,000 workers, or about 16% of the labor force. Since the outbreak of war on October 7, 2023, the number of agricultural workers has risen by about 25%, due to a sharp decline in employment opportunities inside Israel.

Abed al-Rahman, a Palestinian agricultural engineer and adviser from the village of Talluza, has worked alongside Moadi for more than 34 years. He is responsible for one of the most sensitive parts of the process: inspecting produce before it enters Israel.

“All produce that goes through the crossings, especially Sha’ar Efraim and Jalameh, is sampled systematically,” he explains. “We check for pesticide residues and conduct microbiological tests on irrigation quality. Everything is sent to the Agriculture Ministry in Beit El before it’s approved for sale. That’s how we maintain quality and safety.”

Even after the October 7 massacre, the professional work never stopped, he says. “Marketing took a hit, but Samir and I continued without interruption. We never stopped.”

One of the key initiatives led by the Civil Administration’s agricultural unit is a shift to integrated and biological pest control. “Instead of dangerous chemical sprays, we’re using insects,” al-Rahman says. “It reduces toxicity, improves fruit quality and allows Palestinian farmers to meet the standards of all markets—Israel and beyond.”

In the village of Jabara, Tair Kader, an agricultural engineer and farmer, points to a series of water ponds. This is where a fish farming project was born, in cooperation with the Civil Administration. “It started as an irrigation pond for greenhouses,” Kader recalls. “I said, why not raise fish as well? Samir took the idea seriously.

“Israeli experts were brought in, aeration systems, filters and generators were installed. The first pond yielded about 2,800 fish, and later six more ponds were built. Today, there are seven fish ponds in the Tulkarm and Jericho areas, with around 40,000 fish, mainly bass. In March, we’ll introduce no fewer than 30,000 new fish. This is a long-term project.”

Tarek Abu-Safaqa, a trader and packing-house owner, markets agricultural produce and employs more than 170 Palestinian farmers. His goods reach nearly every household in Israel. “The high quality didn’t emerge overnight,” he says. “Even 20 years ago, Israelis and Palestinians were working together to the same standards. It’s the same method, the same know-how.”

On the Israeli side as well, agriculture is seen as a strategic tool. Capt. Yuval Arviv, commander of the Sha’ar Efraim liaison office in the Civil Administration, puts it plainly: “Agriculture is a first line of defense. Without an economy and without jobs, security falls apart. Israel has a clear interest here.”

Since losing his son, Moadi has also led agricultural and landscape memorial projects in memory of fallen Israeli soldiers. “In the end,” he says, looking out over the fields, “life wins. The land doesn’t ask who you are. It asks that you care for it. And if we care for it together, maybe we’ll heal as well.”

And between a greenhouse and a fish pond, between a strawberry field and a crossing gate, it seems that at least here, the land still knows how to bring people together.

The post”the Palestinian farmers feeding I” is auto generated by Nepalisrael.com’s Auto feed for the information purpose. [/gpt3]